Government efforts to reform India’s agricultural sector have divided opinions and sparked debate over the state of Indian agriculture. In the context of this debate, two long-standing features of Indian agriculture stand out.

- First, Indian agriculture is not profitable. Second, it has been heavily regulated by the government and protected from the free play of market forces.

- According to the government, the new bills passed by Parliament attempt to facilitate the sale and production by farmers for the private sector.

- The hope is that liberalizing the sector and allowing greater interplay of market forces will make Indian agriculture more efficient and profitable for farmers. In this context, it is important to understand some of the basic concepts of Indian agriculture.

Participations, income and debts

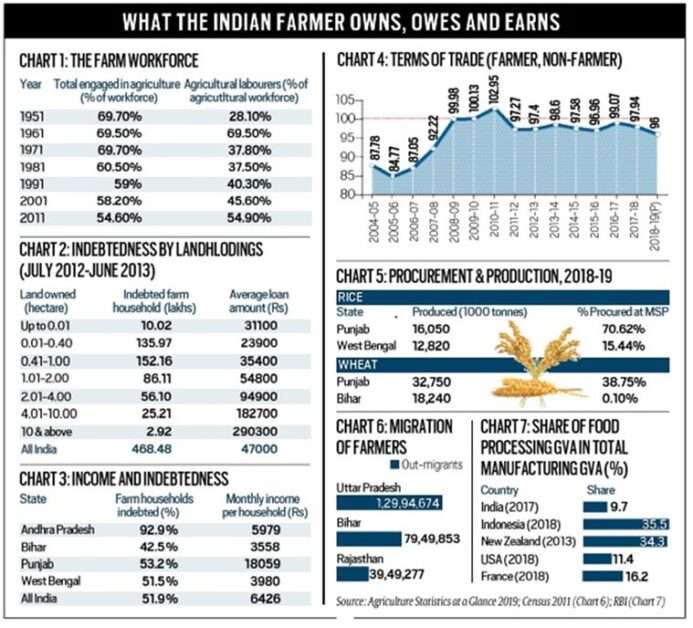

At the time of independence, around 70% of India’s workforce (just under 100 million) was employed in the agricultural sector. Even then, agriculture and related activities accounted for about 54% of India’s national income.

- Over the years, the contribution of agriculture to national production has been greatly reduced. In 2019-20, it was below 17% (in terms of gross value added).

- And yet, the proportion of Indians engaged in agriculture fell from 70% to only 55%.

- As the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income (2017) observes, “the dependence of rural labor on agriculture for employment has not diminished in proportion to the decline in the contribution of agriculture to GDP ”.

- A crucial statistic is the proportion of landless workers (among those involved in this sector), as it reflects the increasing level of impoverishment. It went from 28% (27 million) in 1951 to 55% (144 million) in 2011.

- Although the number of people dependent on agriculture has increased over the years, the average size of the properties has been drastically reduced, even to the point of not being able to produce efficiently.

- Data shows that 86% of all land in India is small (between 1 and 2 hectares) and marginal (less than one hectare, about half a football field). The average size of marginal farms is only 0.37 ha.

- According to a 2015 study by Ramesh Chand, now a member of Niti Aayog, a plot of less than 0.63 ha does not provide enough income to stay above the poverty line.

- The combined result of several of these inefficiencies is that the majority of Indian farmers are heavily indebted. Data shows that 40% of the 24 lakh households operating on land of less than 0.01 ha are in debt. The average amount is 31,000 rupees.

- A good reason why such a high proportion of farmers are so in debt is that Indian agriculture, for the most part, is not remunerative. Figure 3 shows the monthly income estimates for a farm household in four very different states, as well as the number for India as a whole.

- Some of the more populous states like Bihar, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh have very low income levels and very high debt ratios. And even the relatively wealthiest states have quite high debt levels.

Buy Sell

Another way to understand the plight of farmers relative to the rest of the economy is to look at the terms of trade between farmers and non-farmers.

- The terms of trade are the ratio of the prices farmers pay for their inputs to the prices farmers receive for their production, said Himanshu, economics professor at JNU. As such, 100 is the benchmark.

- If the ToT is less than 100, it means the farmers are worse off. As shown in Figure 4, ToC improved rapidly between 2004-05 and 2010-11 to exceed the 100 mark, but has since deteriorated for farmers.

- A key variable in the debate is the role of minimum support prices. Many protesters fear that governments will cancel the MSP system. The MSP is the price at which the government buys a crop from a farmer.

- Over the years, MSPs have achieved several goals. They pushed farmers towards the production of essential crops needed to achieve basic self-sufficiency in food grains. PSMs provide “guaranteed prices” and an “assured market” to farmers and protect them from price fluctuations. This is crucial because most farmers are not sufficiently informed.

- But although PSM is advertised for around 23 crops, actual purchases are very low for crops like wheat and rice.

- Furthermore, the percentage of public contracts varies greatly from one state to another (Figure 5). As a result, real market prices, what farmers get, are often lower than those of the PSM.

Other variables

- These trends in revenue, debt, and acquisitions are aligned with interstate migration. Table 6 shows the states that experience the highest emigration.

- Finally, the government hopes that these reforms, including facilitating the storage of food products, will boost the agri-food industry. An RBI study found that India has plenty of room to develop in this regard and generate jobs and income.

More Stories

Registration for CLAT 2025 begins today; last date October 15

CLAT 2025 registration will begin on July 15

Delhi University 5 Year Law Programs Registration Begins